Photo by Colourbox. All rights reserved.

Photo by Colourbox. All rights reserved.

“One of the smartest VCs has a ominous warning for the tech industry“: Business Insider on Sep, 15. Ten days later: “Another top investor sounds the alarm”. People in the startup community are getting used to announcements of large startup exists or incredibly high venture capital rounds. So, one question arises: Are we in another bubble?

The question is not as up-to-date as the two Business Insider articles may make you believe. There is this funny song about a bubble going around in the valley, dated back to 2007. This was the time when Facebook closed some very awesome deals.

The makers of this video saw another bubble coming in tech industry. They were proven wrong till today, right?

This Time Is Different, Right?

The most important characteristic of a bubble is that you can see it only when it bursts. As long as the music plays, people stay at the party. And the hangover will be epic. Retrospectively, everything seems as it was too simple: Everyone always knew that the party will not last forever. But it turns out that the mechanics of a bubble have the same patterns over and over again.

On the other hand: It is possible that we are just discovering a new era which will (and maybe already has) changed our lives: Some kind of digital industrial revolution? Web 3.0? Industry 4.0? No one would ever call the rise of the automobile industry a bubble. Can we call those internet startups a bubble, then?

Characteristics of sustainable companies

When trying to state that we are in a bubble, people often tend to compare good old blue chips with the valuation of startup rockstars. The video above makes that reference:

Facebook: $ 15.0 billion

Ford: $ 16.8 billion

That’s obviously not a good bubble indicator: How much of your time do you spend in your Ford and how much of your time do you spend on Facebook, their mobile messenger or on the web logging in “with Facebook”? I guess, this round goes to Facebook. Or Google. But not Ford.

So, basically, a huge amount of tech startups build products people love. A good starting point for sustainable companies.

This is the main difference to the dot-com bubble: Pets.com, an often cited “victim” of the bubble and a retail store for pet accessories and supplies, simply did not have customers in those early internet days. It turned out that most of the pet owners simply did not have an internet connection.

But wait, Ford will charge you for your new Mustang, right? And Facebook’s membership is free. Ok, but they have found someone who is paying. It’s just another kind of business model. And Facebook’s costs for a single user profile may be a little bit lighter than those of a Ford Raptor. Other startups out there found services people are willing to pay for and do not solely rely on advertising income.

Next no-bubble-indicator: Some companies make profit, at least they claim so in their business plans. Ok, but what about those startups not having a clue on how to monetize and still get funded? That alone is not a bubble-indicator. If there is a justified assumption that a company may get traction, and thus attention (the currency of media), the bet on future money-making opportunities is just the Venture in Venture Capital.

What drove investors dot-com era?

Investors in the 90ies were driven by the sheer excitement the early internet has brought us. The whole financial was shocked to the core by the aftermath of the 1987 crash, still. The rise of the personal computer and the early days of the internet with its impressive growth rates were seen as the saviors of those bad days.

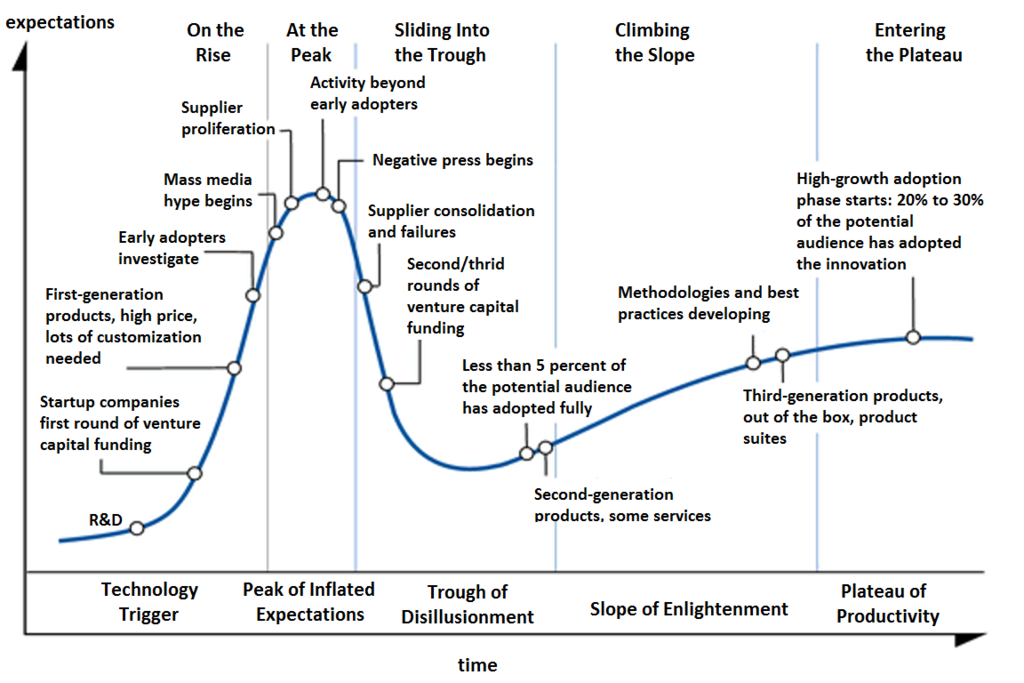

In 1995, Jackie Fenn, consultant at Gartner, presented the so-called Hype Cycle.

Picture by NeedCokeNow - CC BY-SA

Picture by NeedCokeNow - CC BY-SA

The mixture of both, a pathological need to even out the losses of the 1987 crash and a huge over-estimation of the internet’s rate of adoption in the general public made up that toxic haze of those days. But the party went on, critical voices were proved wrong, it seemed. The ingredients for the perfect bubble.

The bottom line of the story: NASDAQ lost nearly 80% in 2002 from its peak in 2000. The rest of the story is history.

What drives investors now?

Technology is now here: We all have those tiny computers in our pocket, we use email way more than letters or fax and nobody would be seen as a nerd for checking restaurant reviews on Yelp.

Technology is simply mainstream now.

The way we use the internet has already changed the way individuals see companies. It is expected to have a always-on support line on any social media channel, companies in turn fear so-called shitstorms and even small business owner start creating high-class content for marketing purposes. They tumble, tweet, blog, whatever.

To put it bluntly, the building blocks of all those expectations projected on the internet are now here.

This situation is a good one for any investor. He simply knows for sure today that tech companies can make a good investment. So, he will invest in business opportunities rather than early adopters of totally unknown “tools”.

Investors of today place a bet on a business model. And not on a business model and the infrastructure needed for the model as they did in the 90ies.

Of course, the internet seems to make it easier to build companies. At least you don’t have to start with a complete factory when you want to build something. A MacBook and a server usually will do the trick (if you look at the number of servers Google operates, you’ll see that’s only one part of the story).

So, it’s clear, that there are simply more business ideas in the tech sector than in traditional capital-binding sectors. More ideas means: More good and bad ideas. So investors should choose wisely whom to fund and when to leave the table.

But, what, if they can’t?

Enter cheap money. A bubble cannot exist if nobody puts money into it. And that point is crucial: Money is available at nearly zero cost.

Chart by economagic

Chart by economagic

When the whole system nearly exploded in 2008 during the so-called “Financial Crisis”, the only answer was an ease in monetary policy. So, states as well as somebig companies are still struggling with debt, while on the other hands some entities simply have too much money at their disposal, needily seeking for an investment opportunity. This in turn makes the “VC market” more competitive. Startups can choose from dozens of potential investors because all of them have a big surplus of private equity funds.

This makes up a completely surreal situation where not the money is the scarce good (and thus, only “good” startups get funded), but in spite of the ease of company creation in the digital space, the good ideas and teams get scarce (and thus, investors are likely to fund whatever they can get).

Over-supply meets over-supply: There is too much cheap money and there is an over-supply of tech ideas (which in turn leads to an under-supply of good tech ideas). Murphy’s law is clear on that: If you accelerate the speed at which things happen, i.e. a startup finds an investor, odds are, that things will not work out.

Conclusion

Clearly, it would be naive to think that we are in the same tech bubble as we were in the dot-com era. Tech industry has just moved forward on the hype cycle curve.

However, we can see the same exaggerations in investments as in other bubbles. The availability of cheap money pushes an enormous pressure on the investors: Since all investors seem to have a huge pile of cash at their disposal, they compete with other investors for the best company to invest in. Money itself is just not the driver of those deals anymore. Investors have to accept smaller shares (and thus, accept exaggerated valuations) and to offer added value to the company, such as expertise and contacts. If they cannot, they have to accept lower quality applications to stay in the game.

That is what Marc Andreessen refers to when he talks about “high burnrates”. However, invest money in high risk companies where you do not know if they will survive is that nature of “Venture Capital”.

At the moment, there is of course a bubble. It is driven by low interest rates (and thus, cheap money) and an under-supply of good investment opportunities. However, this does not affect the tech industry only. It is a common problem in an economy needily craving for opportunities in a zero interest rates environment.

For the tech scene, this time is different.

For the economy, this time is not different at all.

tl;dr Too much cheap money + too much cheap ideas = ingredients for another bubble.